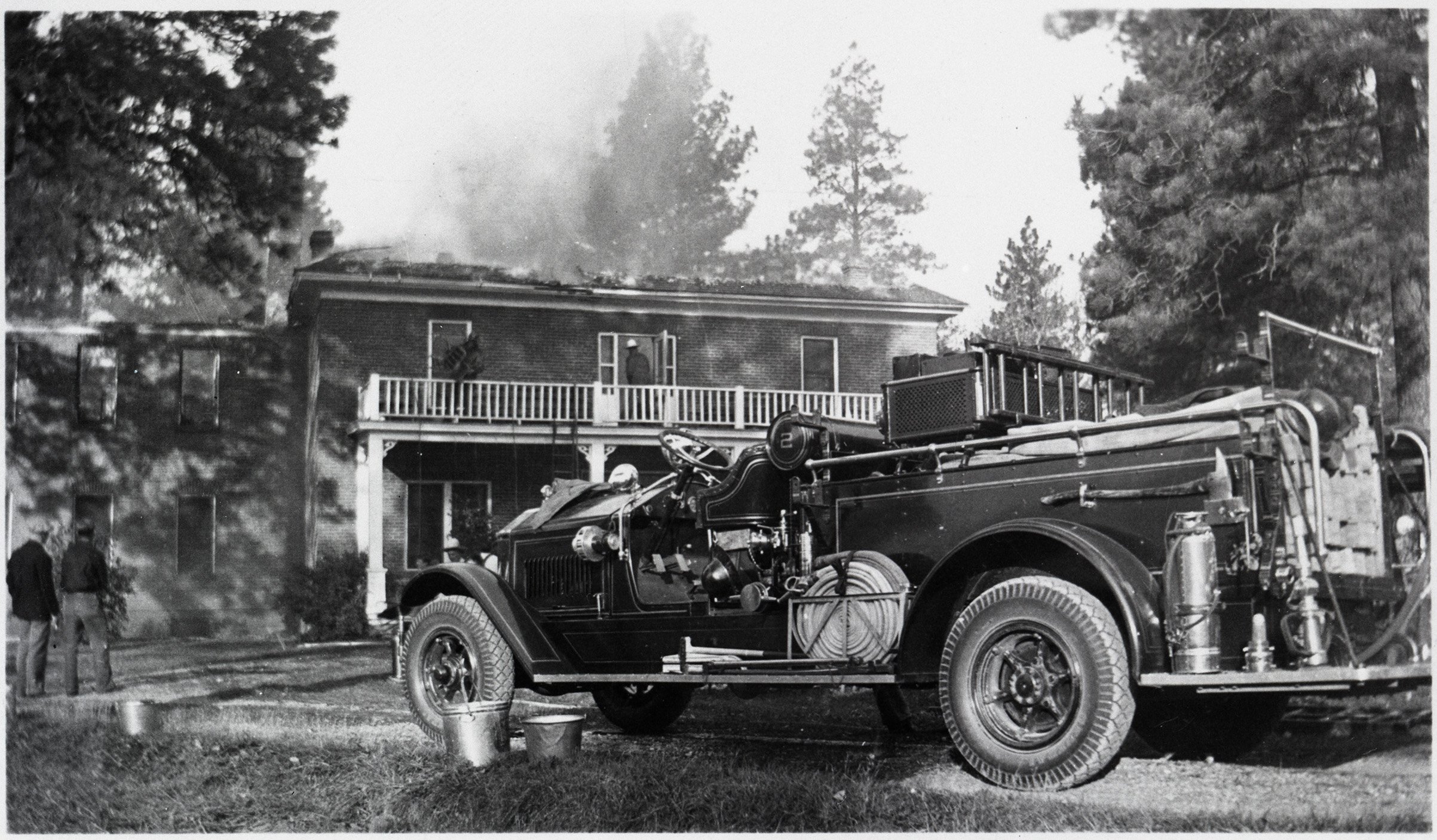

“Fire at Poor Farm up the Rattlesnake,” 1936. The Poor Farm house was built in 1888 and designed by A. J. Gibson. Photo courtesy of Archives and Special Collections, Mansfield Library, University of Montana.

Pest Houses, Poor Farm, Detention Hospital, and Burial Grounds: The Story of Pineview

by Beth Judy

Starting in 1888, the place where Missoula sent its poor residents who were homeless or seriously ill—to live and/or to die—was two and a half miles up the Rattlesnake. There, in 1888, the County bought forty acres along the creek and built, over the next 10 years, three sets of facilities: a Poor Farm, similar to a nursing home, for indigent people (building designed by A. J. Gibson); an assortment of small shacks known as pest houses, where people with serious communicable diseases lived in isolation; and a larger Detention Hospital, finally closed in 1963 and demolished 8 years later. Today, Rattlesnake School, Pineview Park, and private residences occupy the former Poor Farm acres.

Such terminology—“pest houses,” “poor farm,” “detention hospital”—was not unique to Missoula. These were terms in use across America at the time.

The Poor Farm property also housed the dead. At first, these included any ward of the County. Also, Chinese residents of Missoula buried their dead on the grounds (note: the term “Chinese” was often applied to any Asian person). In 1908, however, the County decreed that Chinese people could no longer be buried in the Poor Farm cemetery unless they were actual Poor Farm residents. Chinese Missoulians continued to bury their dead on the property, but segregated in the northeast corner.

In early days, the Rattlesnake was thinly settled. The Poor Farm property was far from town, and the County commissioners liked it that way: out of sight, out of mind. Few funds were allocated for the care of Missoula’s most vulnerable populations. The information in this article comes from the fine book by Rattlesnake resident Steve Smith, Pineview, about the facility and also about a nurse named Marie McNeilly. McNeilly arrived at Pineview in 1947 and reversed over fifty years of suffering and abandonment. Constantly she battled the County’s apathy towards Missoula’s often elderly poor, demanding more resources. She said, “When I’d look at a lot of those old people and talk to them, I felt that they had really started the town of Missoula, which is now the city of Missoula. And they’d done a mighty fine job. They made it a better place for me to live and to enjoy and to raise my daughter. I was very grateful to those people for what they contributed to people who are living today.”

Residents who had no one to care for them filled out an application to live at the Poor Farm. Stays ranged from days to years. Most residents were male; the County sought gentler arrangements for women. At first, a nun ran the Poor Farm, followed by a series of other administrators who often enacted their bosses’ attitude of neglect. When McNeilly first entered the building in 1947, residents had not had linens changed in weeks. Food was terrible, and scarce. Doctors “came up from Missoula” only rarely, e.g., every 2 to 3 weeks. The city hospital did not accept people with serious communicable diseases, hence the pest houses. Their residents were charged the same as for hospital care.

In 1936, a fire ravaged the Poor Farm building and the former pest houses, leaving only the hospital building. It was there that Marie McNeilly arrived in 1947, brought by a County commissioner interviewing her for the job of administrator. At the time, the hospital had 33 patients. When the commissioner opened the door, the smell was so atrocious, he pushed McNeilly in and left. The current administrator was passed out drunk. Maggots wriggled in patients’ bed sores.

Outraged, after taking the job McNeilly not only shamed the County into providing more money for the hospital, she hired excellent staff, demanded good wages for them, and established rigorous standards of cleanliness and care. In time, patients saw the hospital as home, referring to McNeilly as “Mrs. Mac” or “Mother.”

After transforming Pineview into a haven, McNeilly retired in the mid to late 1950s. Later, she wrote, “’the county poor farm’ will soon be a term completely forgotten. As it begins to die, one can see the standard of living among our old people rapidly being elevated.” Many today might question that, but the difference made, for example, by the advent of Social Security in 1948, gladly witnessed by McNeilly among her patients, is inarguable.

Monument honoring the Poor Farm dead, created in 1992 by Rattlesnake School teachers and students. Behind (northwest of) the school building.

Close-up, school monument.

Burials ceased on the Poor Farm property in the 1920s. Between then and the early 1960s, knowledge of the graves seems to have melted away since, when Rattlesnake School was built circa 1960, discovery of graves made the news. From then on, Rattlesnake students knew, via rumor, that their school occupied a former graveyard. In 1989, when a second gym and more classrooms were added, the uncovering of more graves halted construction. Remains were moved, spurring research on the cemeteries and burials. Many burials had occurred without fanfare or even record, but documents from at least one funeral home showed at least 487 burials on the Poor Farm grounds. Extrapolating from there, numbers were probably closer to 750 or even 1,000. People interred at Pineview reflected early Missoula settlement. All races were represented: white, Native American, Asian, African-American—though as noted earlier, after 1908, Asians were segregated. Agewise, the dead ranged from infants to a high proportion of elderly. The largest number of interments in one year (63), at least in the funeral home’s records alone, occurred in 1908 during a typhoid epidemic.

In 1992, Rattlesnake School art teacher Susanne Woyciechowicz saw an opportunity for students to “learn about memorials and think about the stages of life and the importance of remembrance.” Fifteen 6th-, 7th-, and 8th-graders designed the monument, which took a year to complete. They created patterns of imagined faces out of cardboard—the faces on the monument today—and Art Feller, School District #1 electrician, spent hours transforming them through welding into metal. Local metalworks, construction, and monument companies donated materials and many, many hours. The students were Josh Dellinger, Juana Cowan-Hay, David Rummel, Mike Hoag, Scott Liles, Casey Sims, Tanna Neeley, Melissa Mundt, Colt Hall, Lacey Rieker, Crystal Palmer, Tom Lind, Matt Campbell, Merritt Brush, and Kaley Peterson. Behind the school, the monument, adorned with faces, honors Pineview’s dead: those who endured neglect, isolation, misunderstanding, and anonymity, as well as those lucky enough, later, to be known and to experience kindness, compassion, and warmth.

According to one informant, water-main work on the property uncovered more bones in 2016. This early Missoula history, in part a story of changing attitudes towards vulnerable people, remains tangible beneath the ground of Pineview Park and Rattlesnake School. We associate the word “hallowed” with spirits, ghosts, and the dead at “Halloween.” “Hallowed” also means honored and sacred. It’s safe to say that this area of the Rattlesnake Valley is hallowed ground. Next time you’re walking, playing, or recreating there, send a quick hello and thank you to our city ancestors, wherever their bones lie now. They might enjoy that!

For more about Pineview’s history, look for Steve Smith’s fine book published by Pictorial Histories. When Steve was in high school in the late 1950s, Marie McNeilly was his neighbor; she encouraged him to come visit Pineview residents. He remembered colorful people and a warm home atmosphere. Thanks to Steve for helping Missoulians remember this history, and also to Roger and Donna Thomas, Mark Fritch at the Mansfield Library Archives, Stan Cohen, John Rimel, Al and Betty Miller, Susanne Woyciechowicz, Eugene Beckes, Bobby Tilton, Don and Melissa Mundt, and nextdoor.commers Kay H., Patti R. S., Emily P., Michael P., Jeff K., Karin F., Nonda B., and Cassie M.

PINEVIEW POOR FARM PROPERTY TIMELINE:

1888, County buys 40 acres to sequester individuals who are indigent or contagious

1888, Poor Farm building, designed by A. J. Gibson, completed

1897, first pest house built (other small buildings may have predated it

1899, second pest house built

1905, A. J. Gibson designs a Poor Farm house addition

1908, Missoula County Detention Hospital (Pineview Hospital) built—successor to the pest houses

1936, Poor Farm house burns, leaving just the hospital

1947, Marie McNeilly arrives

Late 1940s into 1950s, local dairy farmers coop leases Poor Farm property for use as a bull farm

1955-58 (?), Marie McNeilly retires

1957, School District buys 5 acres for Rattlesnake School construction. It already owns one on the property.

1960, County sells more of the Poor Farm property, e.g., for private residences. Rattlesnake School built around this time. First of the Poor Farm burials found during construction.

1963, Pineview Hospital closes; patients moved to area nursing homes

1971, hospital building demolished

1989, more graves found during school construction

1992, Rattlesnake School teachers and students honor Poor Farm cemetery dead with memorial

2016, more burial sites discovered during water-main work